Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (1804–1892) was a French scholar and draughtsman whose use of photography while he was active in the Middle East pursuing archaeology and studying ancient architecture has made him recognized as an important early photographer. His daguerreotypes are the earliest surviving photographs of Greece, Palestine, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey. After his death in 1892, his carefully stored photographs were discovered in the attic of his estate in the 1920s and they only became known as important works eighty years later.

Girault first announced his intention to study “monuments” of the Mediterranean and their relationship to medieval architecture at a Parisian meeting of the Société française d'archéologie in 1841. He detailed his itinerary and mentioned his use of the daguerreotype the following year. Although somewhat off the beaten track, his journey was not unprecedented and was partially modeled on that of the artist Prosper Marilhat, a fellow member of his Parisian social club, the Cercle des arts. This group, which included painters familiar with the daguerreotype, might also have served as Girault’s point of introduction to photography.

Girault departed from Paris with more than one hundred pounds of photographic equipment, plates, and chemicals in February 1842. He then sailed by steamship from Marseille to Italy, arriving in the Papal States, by way of Genoa, in April. He traveled by boat as much as possible throughout his journey to ease the transport of his supplies. His Roman sojourn is partially documented in letters written by the director of the Académie de France in Rome, which report that the industrious artist had made more than three hundred daguerreotypes by the time he left the city in mid-July, photographing “everything that passed.”

After leaving Italy, Girault made his way to Athens, where he spent the rest of the summer (about six weeks) before traveling on to Egypt in September. He wrote to a colleague at the Société française d’archéologie with enthusiasm about his work in Athens: “I lost less time [than in Rome], and, by my faith, I left very little behind.”

Girault’s use of plates during this part of his excursion was anything but frugal. He appears to have produced more whole plates in Greece than in any other Mediterranean location. Athens was less familiar to Europeans than Rome, and the French were also fascinated by Greece’s recent revolution: Greeks had won independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, and the government moved to Athens in 1834.

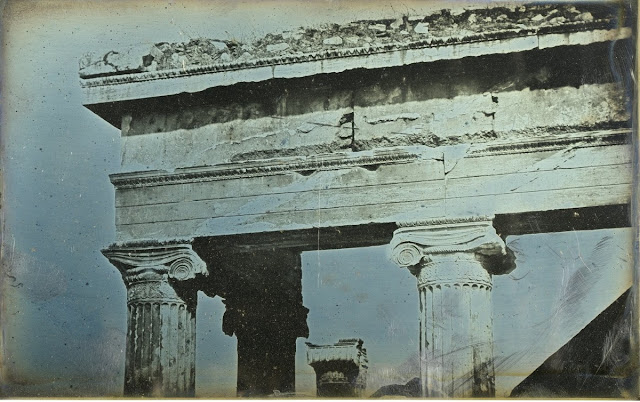

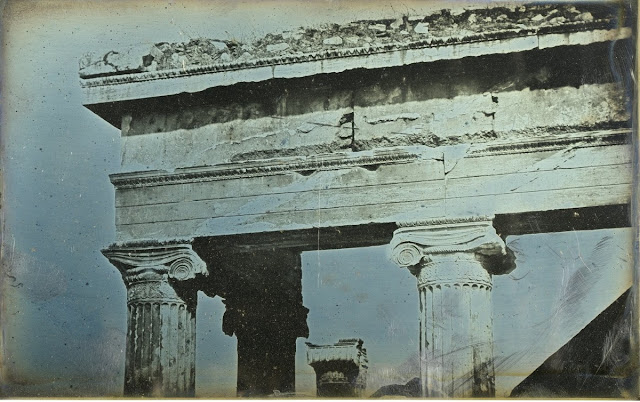

Girault concentrated on the area around the Acropolis. He described his demanding work there—from calculating exposure times to manipulating noxious chemicals in variable conditions—as a rewarding yet challenging photographic campaign: “Nothing in the world is as marvelous or perfect as all that is contained by the Athenian acropolis! As you might guess, the strongest battle occurred there, and God knows how I exerted myself to take my share of the spoils.”

Egypt in the early 1840s was still part of the Ottoman Empire, although it had grown increasingly independent under the leadership of the wali (viceroy) Muhammad ‘Ali. French presence in Egypt had been on the rise since Napoleon’s military campaign (1798–1801) and ‘Ali, a renegade commander from the Ottoman army, formed close ties with French military officers and intellectuals as part of his modernizing efforts. Access to the country had improved in 1835, when Alexandria became the port of entry for the first regular Egypt-bound steamer from Europe.

Girault arrived at the port in the autumn of 1842 and, after exploring Alexandria and nearby Rosetta, he settled in Cairo for the rest of the year. He carefully studied the medieval funerary domes and minarets, which had flourished in the Mamluk period (1250–1517), but he also paid special attention to the first mosque built in Egypt, the Mosque of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As. His photographs of its windows relate to a culturally biased debate among European historians at the time about whether the ogive, or pointed arch, was Islamic or French in origin.

|

| Tower of the Winds, Athens |

|

| Stoa, Athens |

|

| Erechtheion, Athens |

|

| Erechtheion, Athens |

|

| Tombs, Avilenea |

|

| Tombs, Avilenea |

|

| Aphrodisia |

|

| City Gate, Aphrodisia |

|

| Columns, Aphrodisia |

|

| Aphrodisia |

|

| Bunarbashi (Troy) |

|

| Theater, Miletus |

|

| Monastery of Daphni |

|

| Rocks, Philae |

|

| Small Temple, Jebel Selseleh |

|

| Temple, Jebel Selseleh |

|

| Karnak |

|

| Image of Sesostris |

|

| Temple, Edfu |

|

| Necropolis of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna |

0 comments:

Post a Comment