In 1928, the American naturalist William Beebe was given permission by the British government to establish a research station on Nonsuch Island, Bermuda. Using this station, Beebe planned to conduct an in-depth study of the animals inhabiting an eight-square-mile (21 km2) area of ocean, from a depth of two miles (3.2 km) to the surface. Although his initial plan called for him to conduct this study by means of helmet diving and dredging, Beebe soon realized that these methods were inadequate for gaining a detailed understanding of deep-sea animals, and began making plans to invent a way to observe them in their native habitat.

As of the late 1920s, the deepest humans could safely descend in diving helmets was several hundred feet. Submarines of the time had descended to a maximum of 383 ft (117 m), but had no windows, making them useless for Beebe’s goal of observing deep-sea animals. The deepest in the ocean that any human had descended at this point was 525 ft (160 m) wearing an armored suit, but these suits also made movement and observation extremely difficult. What Beebe hoped to create was a deep-sea vessel which both could descend to a much greater depth than any human had descended thus far, and also would enable him to clearly observe and document the deep ocean’s wildlife.

Beebe’s initial design called for a cylindrical vessel, and articles describing his plans were published in The New York Times. These articles caught the attention of the engineer Otis Barton, who had his own ambition to become a deep-sea explorer. Barton was certain that a cylinder would not be strong enough to withstand the pressure of the depths to which Beebe was planning to descend, and sent Beebe several letters proposing an alternative design to him. So many unqualified opportunists were attempting to join Beebe in his efforts that Beebe tended to ignore most of his mail, and Barton’s first efforts to contact him were fruitless. A mutual friend of Barton’s and Beebe’s eventually arranged a meeting between the two, enabling Barton to present his design to Beebe in person. Beebe approved of Barton's design, and the two of them made a deal: Barton would pay for the vessel and all of the other equipment to go with it, while Beebe would pay for other expenses such as chartering a ship to raise and lower it, and as the owner of the vessel Barton would accompany Beebe on his dives in it.

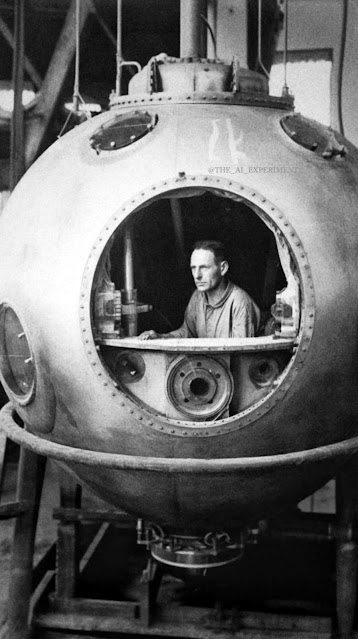

Barton’s design called for a spherical vessel, as a sphere is the best possible shape for resisting high pressure. The sphere had openings for three 3-inch-thick (76 mm) windows made of fused quartz, the strongest transparent material then available, as well as a 400-pound (180 kg) entrance hatch which was to be bolted down before a descent. Initially only two of the windows were mounted on the sphere, and a steel plug was mounted in place of the third window. Oxygen was supplied from high-pressure cylinders carried inside the sphere, while pans of soda lime and calcium chloride were mounted inside the sphere’s walls to absorb exhaled CO2 and moisture. Air was to be circulated past these trays by the Bathysphere’s occupants using palm-leaf fans. The design was originally called a “tank,” “bell,” or “sphere.” Beebe coined the name “bathysphere” using the prefix of the genus Bathytroctes.

The casting of the steel sphere was handled by Watson Stillman Hydraulic Machinery Company in Roselle, New Jersey, and the cord to raise and lower the sphere was provided by John A. Roebling’s Sons Company. General Electric provided a lamp which would be mounted just inside one of the windows to illuminate animals outside the sphere, and Bell Laboratories provided a telephone system by which divers inside the sphere could communicate with the surface. The cables for the telephone and to provide electricity for the lamp were sealed inside a rubber hose, which entered the body of the Bathysphere through a stuffing box.

After the initial version of the sphere had been cast in June 1929, it was discovered that it was too heavy to be lifted by the winch which would be used to lower it into the ocean, requiring Barton to have the sphere melted and re-cast. The final, lighter design consisted of a hollow sphere of one-inch-thick (25 mm) cast steel which was 4.75 ft (1.45 m) in diameter. Its weight was 2.25 tons above the water, although its buoyancy reduced this by 1.4 tons when it was submerged, and the 3,000 ft (910 m) of steel cable weighed an additional 1.35 tons.

|

| Otis Barton (left) with William Beebe. Together, they championed and built a spherical diving submersible which Beebe described as a “bathysphere,” from the Greek “bathus” meaning “deep” and “sphaira” or “sphere”. |

|

| William Beebe and Otis Barton with the Bathysphere. |

Beebe and Barton conducted their first test of the sphere on May 27, 1930, descending to the relatively shallow depth of 45 ft (14 m) in order to ensure that everything worked properly. For a second test, they sent the Bathysphere down unmanned to a far greater depth, and found after pulling it up that the rubber hose carrying the electrical and phone cables had become twisted forty-five times around the cable suspending the Bathysphere. After a second unmanned test dive on June 6 in which the cord did not become tangled, Beebe and Barton performed their first deep dive in the Bathysphere, reaching a depth of 803 ft (245 m).

Beebe and Barton conducted several successful dives during the summer months of 1930, documenting deep-sea animals which had never before been seen in their native habitats. During these dives, Beebe became the first person to observe how as one descends into the depths of the ocean, some frequencies of sunlight disappear before others, so that below a certain depth the only colors of light that remain are violet and blue. Beebe and Barton also used the Bathysphere to perform shallower “contour dives,” mapping Bermuda’s underwater geography. These were particularly dangerous due to the possibility of the Bathysphere smashing against the underwater cliffs which Beebe was mapping, and Barton installed a rudder on the Bathysphere in order to better control its motion during these dives.

On June 16, in honor of Gloria Hollister’s 30th birthday, Beebe allowed her and one of his assistants, John Tee-Van, to perform a dive in the Bathysphere to a depth of 410 ft (120 m), setting a world record for a dive by a woman. Hollister and Tee-Van pleaded to be allowed to descend deeper than this, but Beebe did not allow it out of fear for their safety. In the fall of 1930 Barton donated the Bathysphere to the New York Zoological Society, the primary organization behind Beebe’s work.

|

| Gloria Hollister, William Beebe and John TeeVan next to the Bathysphere, 1932. |

|

| William Beebe (left) and John T. Vann with Beebe’s bathysphere, 1934. |

|

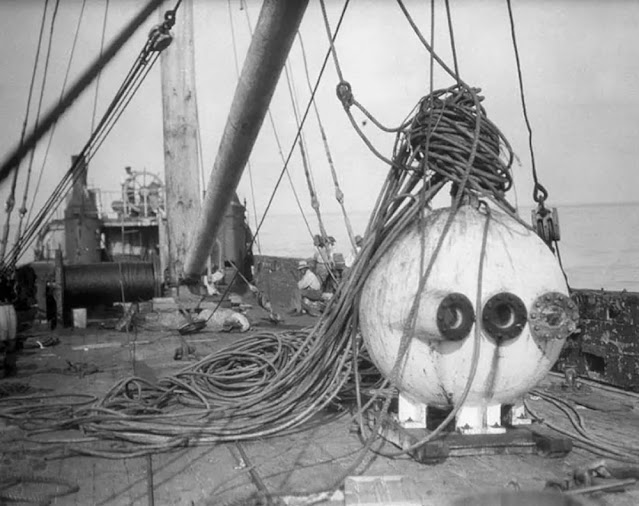

| The Bathysphere being lowered into the ocean, 1932. |

|

| The Bathysphere being raised above the surface. |

|

| Cross-sectional view of the Bathysphere. |

Their dedication to exploring and documenting the deep-sea environment paved the way for future marine biologists and oceanographers to delve even deeper into the ocean's depths.

ReplyDeleteThe images of back sea exploration by submarine are very interesting.

ReplyDelete