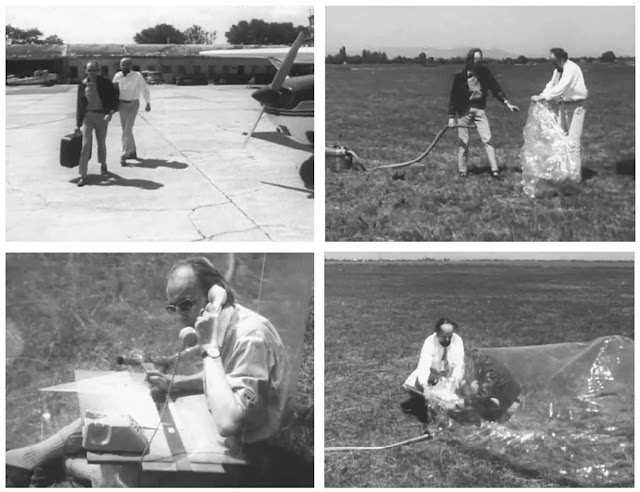

In 1969, years before mobile-communication had developed its possibilities, Austrian architect Hans Hollein built an inflatable mobile office that could be carried around and set up practically anywhere. Prophesying what would later become a laptop, the project—part pneumatic architecture, part performance, part video art—involved Hollein landing a small airplane on a runway and setting up the portable, plastic space, in which he could be seen talking on the telephone and typing.

At the time, Hollein’s Mobile Office explored the social and architectural possibilities brought on by the advancement of new technologies. But it also forecasted their implications for the new worker and the way labor would be effected by an increasingly automated environment. In showing the potential for work to be exported virtually anywhere, Hollein’s performance anticipated the shifting promises offered by modernity from one of spare time and leisure, to a life full of work. In the following essay by Andreas Rumpfhuber, the author explores Hollein’s paradigmatic project in order the understand these workplace disruptions as they relate to the practice of architecture, in particular.

“The idea of the ‘portable house’ derives from today’s way of living, of increased mobility of every man. And modern man that today changes/alters from place to place, does no longer stay in one box, but wants to carry around with him different dwellings. It already happens in a more conventional form, in the form of a trailer that I can bring with me. The ‘portable house’ is the extreme form of an inflatable object, it is an object that I can fold to fit into a suitcase and take with me. Everywhere, where I find a hoover or compressed air I can inflate this structure. I can crawl into it and get shelter.”

Hans Hollein’s Mobile Office has been catalogued as an installation consisting of PVC-foil, a vacuum cleaner, a typewriter (Hermes Baby), a telephone, a drawing board, a pencil, rubber, and thumbtacks. In fact, Mobile Office is a two-minutes-and-twenty-seconds-long performance exclusively produced for television. It paradigmatically shows the contours of an emerging shift in architectural practice that must be read in parallel to the radical transformations in the organization of labour in the postwar years. It is exactly then that the Fordist business organization in Western industrialized countries, with its hierarchic structures, becomes fragile in favor of a new workers’ society.

0 comments:

Post a Comment